|

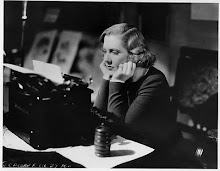

| Ms. Barbara Stanwyck |

Monday, February 28, 2011

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

It's a Black & White Thing (a.k.a. Give Noir a Chance)

Bennett. Lang. Siodmak. Gilda. Bogie & Bacall. Bogie. Chandler. Gin. Guns. Money. Stanwyck. Stanwyck. Stanwyck. Third Men. Widmark. Lupino. Mann. Smoke. Despair. Grahame. Lake & Ladd. Big Heats. Big Streets. Big Combos. Mitchum. Lorre. Greenstreet. Savage. Hammer....

Three of us were in the car listening to Radiohead's latest album, In Rainbows. One friend complained that he missed the days of The Bends and "Creep", and the other professed his undying loyalty by claiming the band had evolved so beautifully over the years. I think I'm somewhere in the happy middle--I love the old stuff, and I love the new stuff. I can't say the same for film noir. As far as the cinema of despair and desperation and myself are concerned, it's black & white or nothing. It's fedoras and trench coats and cigarettes and cramped train compartments and gin and venetian blinds and all of it--or nothing at all. Don't hand me Bullitt, or The French Connection, or Memento, because I'm not buying it. What makes noir so special is that it came and it went, and we can never have it back. Like cigarettes and Nick Charles's drinking. Unless, of course, we keep it around long enough to keep going back to.

Three of us were in the car listening to Radiohead's latest album, In Rainbows. One friend complained that he missed the days of The Bends and "Creep", and the other professed his undying loyalty by claiming the band had evolved so beautifully over the years. I think I'm somewhere in the happy middle--I love the old stuff, and I love the new stuff. I can't say the same for film noir. As far as the cinema of despair and desperation and myself are concerned, it's black & white or nothing. It's fedoras and trench coats and cigarettes and cramped train compartments and gin and venetian blinds and all of it--or nothing at all. Don't hand me Bullitt, or The French Connection, or Memento, because I'm not buying it. What makes noir so special is that it came and it went, and we can never have it back. Like cigarettes and Nick Charles's drinking. Unless, of course, we keep it around long enough to keep going back to.

If asked why I love film noir so much, I doubt I could come up with an answer to satisfy the noir-virgin. I would just tell them to watch Road House and The Third Man and In a Lonely Place and expect them to get it because those are the films that made me get it. Noir made Mitchum vulnerable. Made Lupino belong. Made Widmark set for life.

Younger folks have an aversion to black & white movies. Actually, so did my grandmother, who grew up on them, so let's just say that black & white films tend to get a bad rap. It wasn't until I caught an episode of I Love Lucy while house-sitting for my mother's co-worker that the assumption that black & white = old, dated, and thus not worthwhile, shifted. I was 17 years old, and no one had ever made me laugh the way Lucille Ball did. I knew I had been missing out, and I have left no black & white stone unturned ever since. Because Ms. Ball supported many of the greats (Ginger Rogers, Tracy and Hepburn) she was the perfect introduction to those pre-Technicolor days. (Her flaming do wasn't such a bad introduction to Technicolor, either.) Eventually, I came across her dabbles in noir: 12 Crowded Hours, and Lured, and The Dark Corner. And I knew I had been missing a stark and vulnerable truth that only lies in what the French termed film noir.

How ironic that my attraction to noir, the genre/movement/style (will there ever be a final consensus on this?) of loneliness and desperation, was sparked by a zany, screwball redhead. I don't know anyone who loves noir. (Save perhaps one.) But sometimes a friend will let me drag them to Noir City, or they'll unknowingly start quoting Mike Hammer lines with a smirk and a grin on the walk home (after professing they did not enjoy Kiss Me Deadly, mind you), or sometimes they'll turn to me, perhaps right after Alida Valli walks past Joseph Cotten without so much as a glance in his direction, with that satisfied look of knowing that they too just saw greatness.

50 per cent of all films made before 1951 are gone forever. If we are to agree that film holds significant cultural and historical value, this value only lasts as long as the film survives, and as long as it is seen. Paolo Cherchi Usai likened the film preservationist to a "physician who has accepted the inevitability of death even while he continues to fight for the patient's life". Poetically pessimistic, and he may have a point. But, odds are, with a physician as determined as that, some of those patients are going to make it.

Please join us in donating to the Film Noir Foundation.

Three of us were in the car listening to Radiohead's latest album, In Rainbows. One friend complained that he missed the days of The Bends and "Creep", and the other professed his undying loyalty by claiming the band had evolved so beautifully over the years. I think I'm somewhere in the happy middle--I love the old stuff, and I love the new stuff. I can't say the same for film noir. As far as the cinema of despair and desperation and myself are concerned, it's black & white or nothing. It's fedoras and trench coats and cigarettes and cramped train compartments and gin and venetian blinds and all of it--or nothing at all. Don't hand me Bullitt, or The French Connection, or Memento, because I'm not buying it. What makes noir so special is that it came and it went, and we can never have it back. Like cigarettes and Nick Charles's drinking. Unless, of course, we keep it around long enough to keep going back to.

Three of us were in the car listening to Radiohead's latest album, In Rainbows. One friend complained that he missed the days of The Bends and "Creep", and the other professed his undying loyalty by claiming the band had evolved so beautifully over the years. I think I'm somewhere in the happy middle--I love the old stuff, and I love the new stuff. I can't say the same for film noir. As far as the cinema of despair and desperation and myself are concerned, it's black & white or nothing. It's fedoras and trench coats and cigarettes and cramped train compartments and gin and venetian blinds and all of it--or nothing at all. Don't hand me Bullitt, or The French Connection, or Memento, because I'm not buying it. What makes noir so special is that it came and it went, and we can never have it back. Like cigarettes and Nick Charles's drinking. Unless, of course, we keep it around long enough to keep going back to.If asked why I love film noir so much, I doubt I could come up with an answer to satisfy the noir-virgin. I would just tell them to watch Road House and The Third Man and In a Lonely Place and expect them to get it because those are the films that made me get it. Noir made Mitchum vulnerable. Made Lupino belong. Made Widmark set for life.

Younger folks have an aversion to black & white movies. Actually, so did my grandmother, who grew up on them, so let's just say that black & white films tend to get a bad rap. It wasn't until I caught an episode of I Love Lucy while house-sitting for my mother's co-worker that the assumption that black & white = old, dated, and thus not worthwhile, shifted. I was 17 years old, and no one had ever made me laugh the way Lucille Ball did. I knew I had been missing out, and I have left no black & white stone unturned ever since. Because Ms. Ball supported many of the greats (Ginger Rogers, Tracy and Hepburn) she was the perfect introduction to those pre-Technicolor days. (Her flaming do wasn't such a bad introduction to Technicolor, either.) Eventually, I came across her dabbles in noir: 12 Crowded Hours, and Lured, and The Dark Corner. And I knew I had been missing a stark and vulnerable truth that only lies in what the French termed film noir.

How ironic that my attraction to noir, the genre/movement/style (will there ever be a final consensus on this?) of loneliness and desperation, was sparked by a zany, screwball redhead. I don't know anyone who loves noir. (Save perhaps one.) But sometimes a friend will let me drag them to Noir City, or they'll unknowingly start quoting Mike Hammer lines with a smirk and a grin on the walk home (after professing they did not enjoy Kiss Me Deadly, mind you), or sometimes they'll turn to me, perhaps right after Alida Valli walks past Joseph Cotten without so much as a glance in his direction, with that satisfied look of knowing that they too just saw greatness.

50 per cent of all films made before 1951 are gone forever. If we are to agree that film holds significant cultural and historical value, this value only lasts as long as the film survives, and as long as it is seen. Paolo Cherchi Usai likened the film preservationist to a "physician who has accepted the inevitability of death even while he continues to fight for the patient's life". Poetically pessimistic, and he may have a point. But, odds are, with a physician as determined as that, some of those patients are going to make it.

Please join us in donating to the Film Noir Foundation.

Labels:

noir

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)