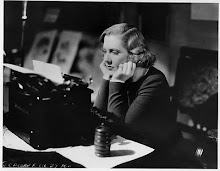

Unleashed from the bizarre mind of Tod Browning, who later crawled under the skin with the cult classics Dracula (1931) and Freaks (1932), The Unknown (1927) is a grotesque, morbid, and, appropriately, little known onyx of a tale. A gem that favors the darker, edgier crevices of attraction rather than beauty’s plush satin comforts. This film crept up on me. It was one of those old-movie-lover late nights when you expect nothing and let go of any reservations or favoritism. You’re up for anything TCM will give you at such a late hour. The credits start rolling: Lon Chaney, Joan Crawford. You sit up, suddenly more attentive, but have no idea what you’re in for, no suspicion of what weird images lurk around the corner. And they do lurk.

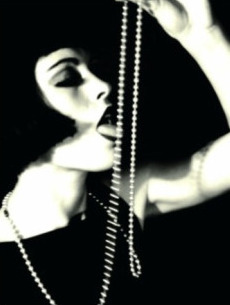

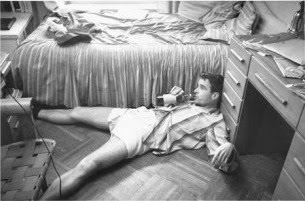

Chaney, the one and only “Man of a Thousand Faces”, plays Alonzo the Armless, whose popular act entails throwing knives with his feet around the carnival owner's daughter, Nanon. He is also madly in love with her. Beautiful Nanon (a fresh faced Joan Crawford before make-up completely concealed her freckles) hardly fits in with the physical deformities surrounding her, but her bizarre and unexplained phobia of men's hands gives Alonzo an obvious advantage, and the circus strongman, Nanon's other suitor, a clear disadvantage.

When it is soon revealed that Alonzo actually owns a very able and healthy pair of arms, complete with attached man hands, the story plunges into a black hole of obsession, murder, and gruesome consequences. It's not until you remember this was pre-Production Code that its shocking developments seem possible. And then you know anything goes; the safety net is gone. This is a weird one, to be sure. Wonderfully weird. The story is one I doubt Hollywood could resist stuffing into a formulaic horror genre, or submitting to the same fate--hasty oblivion--as the similarly cliché-bound remakes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Dial M for Murder (re-titled A Perfect Murder in 1998). This is a film that needs black and white, that needs silence, and that can't be overdone with sentimental whims or bloody carnage. It is also a film that reveals these things can work--subtlety and control--and it's a pity modern Hollywood doesn't recognize that more often.

I love this film because it's weird, because Lon Chaney is always remarkable, and because it does things I've never seen done before. It may not be a film that is instantly thought of as one of either Chaney's or Browning's crowning achievements (perhaps forever stuck in the shadow of The Phantom of the Opera (1925) and Freaks) but that seems almost as it should be. It's like a hidden secret you're delighted to be a part of. And an old secret--one that was around long before the horror genre cut its celluloid teeth, and long before the fully morphed serial killers and monsters under the bed. It hovers like a dark foreshadowing of what awaits us. And it's not pretty. It's deliciously sinister.