Saturday, January 22, 2011

I Couldn't Have Said It Better Myself

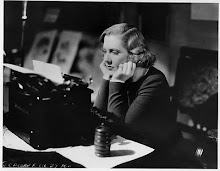

Movie Morlocks' fantastic review of Hitchcock's underrated Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941), with Carole Lombard & Robert Montgomery.

Equally fantastic essay on the intense and phenomenal I Want to Live! (1958) from the Film Noir Foundation's Noir City Sentinel.

And a great post on the classic Ball of Fire (1941) by my new favorite film blogger.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Ring Out the Old Year, Ring in the New, Ring-A-Ding...ah, nevermind.

The other day I was struck by the sudden urge to revamp this ol' blog of mine. Changing your blog can be like changing your hair, or rearranging your furniture, and I felt like such a change was needed to celebrate the New Year, or make official this spreading feeling that 2011 is going to be the year of greatness, and change, and possibility. Or, maybe that was just an excuse to avoid job searching, and washing the dishes, and doing the laundry. Either way, I spent hours perusing these new fangled templates Blogger now has: abstract background images (red curtains? no, that doesn't quite work, though I appreciate the suggestion of a movie theater- Oh, Castro, I miss you!), raindrops (uhh...), motorcycles (no, thank you), and on and on and on. Then there are the overwhelming choices of color, font, font size, layouts, borders, etc. etc. And while I tried several of these out, and even liked a few, comparing them to my blog's current "look" just made me miss the white on black noir-ness, the rather dramatic borders, the wide layout that allows for bigger (and better) images, and the color scheme that took me months to work out. And then I thought, fuck it! I like the way things are. (And I am spending way too much time on this.)

So, I raise my glass of pinot and make a toast to un-change, or at least to realizing that things are not so bad, and rather quite good when you take notice of them:

(Btw, SPOILER! Seriously, watch the movie instead.)

So, I raise my glass of pinot and make a toast to un-change, or at least to realizing that things are not so bad, and rather quite good when you take notice of them:

(Btw, SPOILER! Seriously, watch the movie instead.)

Labels:

billy wilder,

jack lemmon,

shirley maclaine

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Noir City 2011

Wouldn't you know it: the first Noir City I'm unable to attend in 4 years, and Eddie Muller & Co. create the most fantastically delicious program ever. (Can't you just tell by that cover photo?) I told myself last year when I moved from the Bay Area, don't freak out! I reassured myself that I would come back every winter for Noir City, no matter what the cost, fully prepared in heels and lipstick. Unfortunately, I've had to face the harsh realization that what they're saying is right: the economy has gone down the drain. Perhaps if I had Ann Savage as a hitchhiking buddy, or Joel McCrea as a fellow train-hopping hobo--heck, I would even take a lift from Richard Widmark--perhaps then I would risk the trek. No, I can only do my best to stifle the painful blow that I'll be missing not one, not two, but three Barbara Stanwyck films (salt in an open wound), a slew of goodies by Litvak, Preminger, Siodmak, Renoir, Cukor, Lang, & Mann (many not available on DVD; here comes that salt), and one of the most chilling noir masterpieces there ever was, Gaslight (1944) (okay, now it's just plain acid). No, I can only ignore the sting, the devil-may-care urge to buy a plane ticket and see what happens, and hope that you folks in the Bay take advantage of this year's festival with the complete understanding that you are lucky sons-of-bitches.

Labels:

noir,

noir city 2011

Saturday, January 8, 2011

Lean's Twist: No Place for Children

I've always associated David Lean with those grand, sweeping, drawn-out epics (film's equivalent to Tolstoy?) and pretty much avoided him. I've never been able to sit through Lawrence of Arabia (1962) in its entirety, and A Passage to India (1984) left me a bit cold. Judy Davis's performance was unusually odd and stifled, and I wasn't surprised to read that she and Lean were regular head-butters. Doctor Zhivago (1965) was beautiful, but not enough to balance the scales in Lean's favor and make me crave more. Luckily, though, and spurred on by my absolute love for Brief Encounter's (1945) simplicity and black-and-white cinematography, my opinion has changed. (Not concerning the epics, but in the realization that Lean's earlier films are works I can appreciate.)

I was lucky enough to catch both Hobson's Choice (1954) and Madeleine (1950) (both Victorian-noirs in the vein of Gaslight [1944] and The Spiral Staircase [1945]) at the PFA's David Lean tribute last year, but it is really his films from the 1940s that provide a wonderful antithesis to his post-'60s extravaganzas. (Two other greats: The Passionate Friends [1949], a sort of companion piece to Brief Encounter, and Great Expectations [1946].) True, Noel Coward probably deserves a lot of credit for this, as he collaborated with Lean on four films from the '40s (including Brief Encounter, which was based on a Coward play), but within the first few frames of Oliver Twist (1948) it's apparent that Lean is quite capable of conducting his own electric and cinematic wizardry.

Of all the film versions of Dickens's Oliver Twist, Lean's is the most beautiful, the most devastating, and the most atmospheric. You can tell that both Carol Reed and Roman Polanski were aware of its importance. Acknowledging that several key scenes from Lean's Oliver had already been portrayed to perfection, both directors chose to include almost exact replicas in their versions. (The boys eating porridge, and looking on, half-starved, as the adults gorge themselves on a fine feast.) Interestingly enough, though, both directors also excluded Lean's infamous opening scene of Oliver's mother arriving at the workhouse. This scene is perhaps the best film opener I've seen. Amid a violent storm: close-ups of twisted, thorny branches, a pregnant young girl clutching the prison-like gates of the workhouse, shadows swallowing her up. The rain, the mud, everything working against her. She is doomed, but, of course, we can't help hope for a miracle.

The entire opening sequence was conceived by Lean's second wife, Kay Walsh, who plays Nancy. Nancy is an interesting character, and used very differently by Lean and Reed. The relationship between Oliver and Nancy is more developed in Reed's Oliver! (1968), however, I can't help but feel that the suspenseful tavern scene in Lean's version does more to establish Nancy's character than the extra screen time given to her by Reed. Lean (and Walsh's) Nancy is more complex. She's more crass, more beaten down, and more concerned with her own survival as the only woman amongst a world of orphan boys and thieving men (both Reed and Polanski give Nancy a girlfriend to hang with; Lean leaves her on her own; I'm not sure which was true to Dickens). Walsh's Nancy also doesn't have the advantage of a musical number to unite her with the used and abused Oliver. You're not quite sure where she stands, but finally recognizing Walsh's transition from indifferent spectator to sacrificial protector is phenomenal. Oliver Reed's portrayal of Bill Sikes in Oliver! is much more successful, creepy/on-the-edge/disturbing-wise, than Robert Newton's in Lean's version, but Walsh's performance (especially in that wonderfully suspenseful tavern scene) hardly allows Newton's less-threatening Bill to detract from her terrifying plight. This is the moment when you really question what you've seen of Bill Sikes, and take note of that underlying violence that's been scratching at the surface the entire time. (And adds a whole new level of horror to his treatment of Nancy later on.) But Nancy is Oliver's mother re-born. Another woman who will die so he can live. She knows it without fully accepting it.

Where Reed favors comedy (his is a musical, after all), Lean favors tragedy and borrows many elements from noir. Lean introduces us to Oliver: a frail, trembling, literally half-starved-looking young boy scrubbing the cold floors all alone. Reed's Oliver is a cherub (his face seems to glow), and, despite tattered rags and bare feet, he is at least surrounded by fellow orphans and friends. Another major difference between the two is the portrayal of Fagin, performed by a pre-famous Alec Guinness in Lean's version, and Ron Moody in Reed's version. Moody's Fagin is goofy, harmless, and selfish while still concerned for Oliver's well-being. When he teaches Oliver to pickpocket, he does it with the full understanding that the lesson should be fun and entertaining, and he relishes Oliver's smiles and giggles. He's not a bad guy, just trying to get along in a harsh reality. Guinness's portrayal is very different, and, I assume, more true to Dickens. His selfishness is discomforting, and he never lets you rest in trying to figure him out. He refuses an understanding that he is either purely selfish, and thus dangerous, or that he is pathetic, and sad, and desperate, and perhaps even more dangerous.

More so than both Reed and Polanski (whose version was a complete dud) David Lean brings Dickens's story to life as a dark and deadly world in which children are at the mercy of the corrupted. At one point in Reed's film, Oliver bows to Fagin with respect. It's treated as a joke, and the other boys laugh at him. In Lean's film, you understand that such behavior has been beaten into him.

I was lucky enough to catch both Hobson's Choice (1954) and Madeleine (1950) (both Victorian-noirs in the vein of Gaslight [1944] and The Spiral Staircase [1945]) at the PFA's David Lean tribute last year, but it is really his films from the 1940s that provide a wonderful antithesis to his post-'60s extravaganzas. (Two other greats: The Passionate Friends [1949], a sort of companion piece to Brief Encounter, and Great Expectations [1946].) True, Noel Coward probably deserves a lot of credit for this, as he collaborated with Lean on four films from the '40s (including Brief Encounter, which was based on a Coward play), but within the first few frames of Oliver Twist (1948) it's apparent that Lean is quite capable of conducting his own electric and cinematic wizardry.

Of all the film versions of Dickens's Oliver Twist, Lean's is the most beautiful, the most devastating, and the most atmospheric. You can tell that both Carol Reed and Roman Polanski were aware of its importance. Acknowledging that several key scenes from Lean's Oliver had already been portrayed to perfection, both directors chose to include almost exact replicas in their versions. (The boys eating porridge, and looking on, half-starved, as the adults gorge themselves on a fine feast.) Interestingly enough, though, both directors also excluded Lean's infamous opening scene of Oliver's mother arriving at the workhouse. This scene is perhaps the best film opener I've seen. Amid a violent storm: close-ups of twisted, thorny branches, a pregnant young girl clutching the prison-like gates of the workhouse, shadows swallowing her up. The rain, the mud, everything working against her. She is doomed, but, of course, we can't help hope for a miracle.

The entire opening sequence was conceived by Lean's second wife, Kay Walsh, who plays Nancy. Nancy is an interesting character, and used very differently by Lean and Reed. The relationship between Oliver and Nancy is more developed in Reed's Oliver! (1968), however, I can't help but feel that the suspenseful tavern scene in Lean's version does more to establish Nancy's character than the extra screen time given to her by Reed. Lean (and Walsh's) Nancy is more complex. She's more crass, more beaten down, and more concerned with her own survival as the only woman amongst a world of orphan boys and thieving men (both Reed and Polanski give Nancy a girlfriend to hang with; Lean leaves her on her own; I'm not sure which was true to Dickens). Walsh's Nancy also doesn't have the advantage of a musical number to unite her with the used and abused Oliver. You're not quite sure where she stands, but finally recognizing Walsh's transition from indifferent spectator to sacrificial protector is phenomenal. Oliver Reed's portrayal of Bill Sikes in Oliver! is much more successful, creepy/on-the-edge/disturbing-wise, than Robert Newton's in Lean's version, but Walsh's performance (especially in that wonderfully suspenseful tavern scene) hardly allows Newton's less-threatening Bill to detract from her terrifying plight. This is the moment when you really question what you've seen of Bill Sikes, and take note of that underlying violence that's been scratching at the surface the entire time. (And adds a whole new level of horror to his treatment of Nancy later on.) But Nancy is Oliver's mother re-born. Another woman who will die so he can live. She knows it without fully accepting it.

Where Reed favors comedy (his is a musical, after all), Lean favors tragedy and borrows many elements from noir. Lean introduces us to Oliver: a frail, trembling, literally half-starved-looking young boy scrubbing the cold floors all alone. Reed's Oliver is a cherub (his face seems to glow), and, despite tattered rags and bare feet, he is at least surrounded by fellow orphans and friends. Another major difference between the two is the portrayal of Fagin, performed by a pre-famous Alec Guinness in Lean's version, and Ron Moody in Reed's version. Moody's Fagin is goofy, harmless, and selfish while still concerned for Oliver's well-being. When he teaches Oliver to pickpocket, he does it with the full understanding that the lesson should be fun and entertaining, and he relishes Oliver's smiles and giggles. He's not a bad guy, just trying to get along in a harsh reality. Guinness's portrayal is very different, and, I assume, more true to Dickens. His selfishness is discomforting, and he never lets you rest in trying to figure him out. He refuses an understanding that he is either purely selfish, and thus dangerous, or that he is pathetic, and sad, and desperate, and perhaps even more dangerous.

More so than both Reed and Polanski (whose version was a complete dud) David Lean brings Dickens's story to life as a dark and deadly world in which children are at the mercy of the corrupted. At one point in Reed's film, Oliver bows to Fagin with respect. It's treated as a joke, and the other boys laugh at him. In Lean's film, you understand that such behavior has been beaten into him.

Labels:

british,

david lean,

literary adaptations,

noir

The Trailers, no. 2

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948)

Labels:

anatole litvak,

barbara stanwyck,

burt lancaster,

noir,

trailers

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)